Modern neuroscience is redefining how we think about aging. Getting older — a process traditionally perceived as a steady decline — can also be considered a natural evolution, thanks to our understanding of the science of neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to form new neural connections throughout our lives. Our brains can adapt to new situations, learn new skills, and recover from injuries, maintaining the vitality of our minds, even as we age.

One of the core neurological phenomena contributing to the resilience of our brains is: cognitive reserve. That might sound complex, but it’s a very simple and powerful concept! Cognitive reserve is the brain’s ability to improvise and find alternative ways of getting a job done.

Much like a busy highway easing congestion by rerouting traffic, our brains can reroute neural pathways around injuries or age-related changes.

But the brain goes beyond simply rerouting — it can also create completely new connections, like a city planning department building entirely new roads to quell traffic problems.

Cognitive reserve is built up over our lifetimes. Every new skill we learn, problem we solve, and book we read contributes to this reserve. It’s like making deposits into a neural savings account for our minds — a safety net that can buffer against potential cognitive decline later in life.

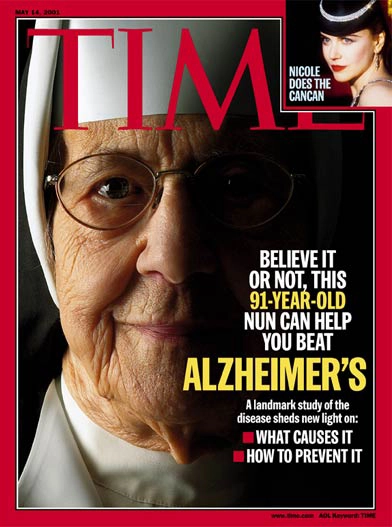

The Nun Study: a classic case of healthy aging

The concept of cognitive reserve isn’t merely theoretical; it’s been observed in real-world scenarios, like the compelling ‘Nun Study’, a piece of landmark research through which scientists discovered that, despite experiencing physical brain changes typically associated with Alzheimer’s disease, some of the nuns who were part of the study were able to maintain cognitive function, as their brains rerouted around the physical changes.

What was the secret to their cognitive resilience? The researchers attributed it to the nuns’ lifelong active engagement in intellectual and social activities. By constantly learning, interacting, and challenging their minds, the nuns had built up a robust cognitive reserve. And it was this buffer — this safety net — that allowed them to maintain cognitive function despite the physical changes in their brains.

Their experience underscores the power of cognitive reserve and the importance of an active, engaged lifestyle in promoting brain resilience.

The London Taxi Driver Study: neuroscience and navigation

I mentioned rerouting traffic… well, this other piece of research is literally called the ‘London Taxi Driver Study’! It showed that the hippocampus — that’s the part of the brain responsible for memory and spatial navigation — was larger in taxi drivers compared to the general population.

The mental workouts they constantly did to remember London’s dense winding streets physically ballooned their hippocampi as new neural connections formed.

How to strengthen your cognitive reserve

You might be wondering: Dean, how can I actively contribute to my cognitive reserve and enhance my own brain’s resilience? One of the most powerful methods: regular physical exercise.

Research has shown that engaging in regular physical activity can stimulate the growth of new neurons, a process known as ‘neurogenesis’.

Physical activity increases blood flow to the brain, delivering more oxygen and nutrients that are essential for brain health.

Exercise also helps to release chemicals which protect our brains, stabilize our mood, and strengthen our ability to focus and concentrate.

This physical activity doesn’t have to be strenuous, though. Walking, cycling, or dancing count! The key is consistency. It’s all about making regular deposits into your cognitive reserve.

So, next time you’re thinking about skipping that workout, remember that committing to the exercise isn’t just benefitting your body — you’re also strengthening your brain. It’s a double-win for your overall health and a significant step towards building a resilient brain.

Another powerful way to build your cognitive reserve and enhance your brain resilience is by pursuing your passions. Engaging in activities we love not only enriches our lives, but also stimulates our brains, keeps us mentally active, and can even help to grow our cognitive capacity.

Let’s take learning to play a musical instrument as an example. This calls for physical coordination, reading music, memorizing sequences, and understanding rhythm and timing. All these elements are comprehensive workouts for the brain, stimulating various areas and building new neural connections.

Similarly, learning a new language is a fantastic way to challenge our brains. It involves understanding new grammar rules, expanding vocabulary, and practicing pronunciation. This cognitive exercise can enhance memory, improve attention, and even boost problem-solving skills.

Dancing, too, is a wonderful brain-boosting activity. It combines physical exercise with the mental challenge of remembering dance steps and sequences. Plus, it often involves social interaction, which is another important factor in boosting and maintaining brain health.

Volunteering is another activity which can contribute to brain resilience. Whether it’s helping out at a local community center, tutoring students, or working on a neighborhood project, volunteering provides social engagement, mental stimulation, and a sense of purpose — all key for brain health.

Even hobbies like gardening, painting, or bird-watching can contribute to cognitive reserve. They require focus, learning, and engagement, which all stimulate the brain.

Activities that challenge you, engage you, and make you happy are an incredibly powerful good for your brain. They help you build cognitive reserve and enhance your brain resilience, enabling you to age with grace and maintain your cognitive vitality.

So, pursue your passions, learn new skills, and embrace lifelong learning. Your brain will thank you for it.

References

Snowdon, D. (2001). Aging with Grace: What the Nun Study Teaches Us About Leading Longer, Healthier, and More Meaningful Lives. Bantam Books.

Maguire, E. A., Gadian, D. G., Johnsrude, I. S., Good, C. D., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R. S., & Frith, C. D. (2000). Navigation-related structural change in the hippocampi of taxi drivers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(8), 4398-4403.

Cotman, C. W., & Berchtold, N. C. (2002). Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends in neurosciences, 25(6), 295-301.

About The Author

Dean Sherzai, MD, PhD

Dr. Dean Sherzai is co-director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program at Loma Linda University. Dean trained in Neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine, and completed fellowships in neurodegenerative diseases and dementia at the National Institutes of Health and UC San Diego. He also holds a PhD in Healthcare Leadership with a focus on community health from Andrews University.

Get more brain science direct to your email inbox

Sign up for the Brain Docs newsletter for weekly recipes, brain teasers, neuroscience facts, podcast updates, and more — for free!