Hypnosis, a term often shrouded in mystery and misconceptions, has a rich history, and promising potential in the realm of neuroscience and therapeutic application. Here, I dive into the practice’s past, and how it can be used to support recovery and better brain health.

“Hypnosis, with its unique ability to access the subconscious mind, offers promising avenues for intervention in challenging areas of clinical psychology.”

Blog Contents

- The origins of hypnosis: Mesmer and magnetism

- Hypnotism gets a murky reputation: past problems, false uses, and dramatic portrayals

- What is hypnosis, scientifically speaking?

- Our current and historic understanding of hypnosis

- The neuroscience of hypnosis

- The suggestibility conundrum: a double-edged sword

- The use of hypnotherapy in clinical and healthcare environments

- The future of hypnosis and hypnotherapy

The origins of hypnosis: Mesmer and magnetism

The tale of hypnosis is as mesmerizing as the practice itself, and its genesis can be traced back to one flamboyant and controversial figure: Franz Anton Mesmer.

In the late 18th century, Vienna-born Mesmer, a physician by profession, proposed a radical theory: he believed in the existence of a mysterious “animal magnetism” — a universal fluid flowing between animate beings and their surroundings.

According to Mesmer, diseases were caused by blockages in this fluid’s flow, and by manipulating it using magnets and hands-on techniques, one could restore health.

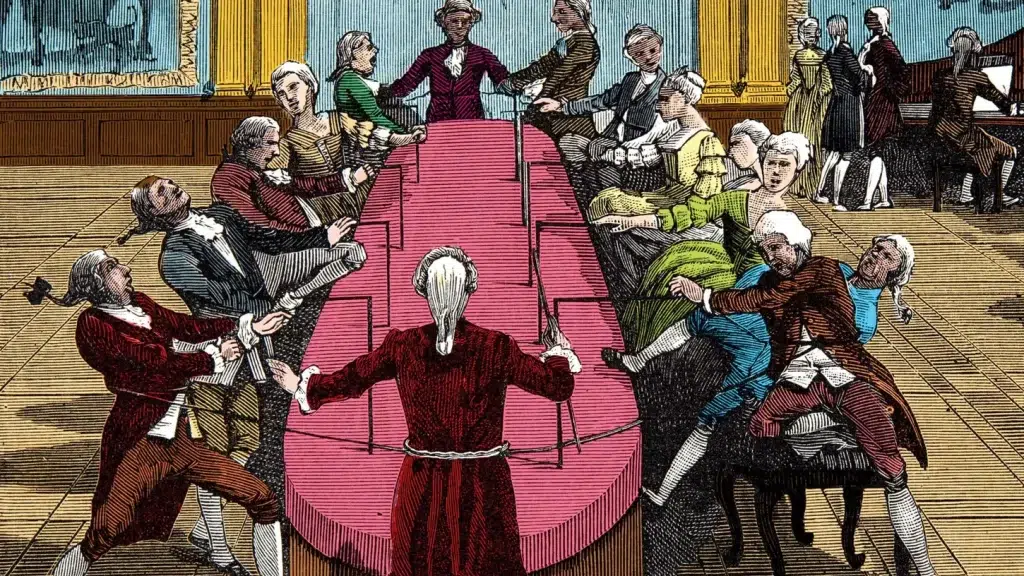

Mesmer’s salons in Paris became the stuff of legends. Picture this: a dimly-lit room filled with the sound of glass harmonicas, patients seated around a “baquet” (a large tub filled with magnetized water) holding iron rods, and waiting for the magnetic fluid to heal them.

The atmosphere was charged, both literally and metaphorically. Many patients reported feeling peculiar sensations and even exhibited convulsions, which Mesmer interpreted as the magnetic fluid working its magic.

While many of the Parisian elite — including Queen Marie Antoinette! — were intrigued by Mesmer’s methods, the scientific community was skeptical.

In 1784, King Louis XVI commissioned a group of leading scientists, including Benjamin Franklin, to investigate Mesmer’s claims. Their verdict? Any benefits from Mesmer’s techniques were due to the power of suggestion, not any magnetic fluid.

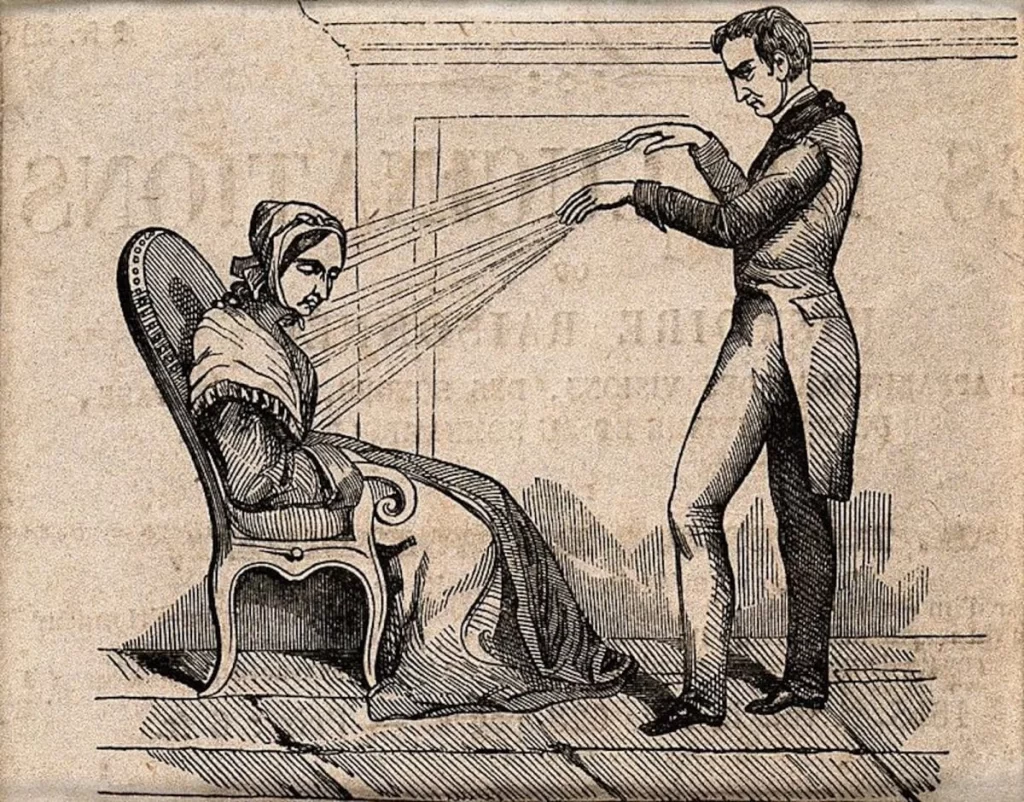

Enter James Braid, a Scottish surgeon in the 19th century, often termed the “Father of Modern Hypnotism”. Braid attended a magnetic demonstration and, while skeptical of the magnetic theories, was intrigued by the phenomena he witnessed.

He believed the effects were psychological and introduced the term ‘hypnotism’, derived from the Greek word ‘Hypnos’ for sleep. Braid’s work shifted the narrative from Mesmer’s mystical magnetism to a more grounded understanding of altered states of consciousness.

In essence, while Mesmer’s magnetic fluid theories were debunked, they set the stage for the evolution of a practice that would delve deep into the mysteries of the human mind.

The theatricality of Mesmer’s salons, combined with Braid’s scientific rigor, provided the foundation for our modern understanding of hypnosis.

Hypnotism gets a murky reputation: past problems, false uses, and dramatic portrayals

The history of hypnosis has been anything but smooth. As it gained traction in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it found itself enmeshed in a web of controversies that threatened its legitimacy.

Spiritualism and séances: During the Victorian era, spiritualism became a widespread fascination, with mediums conducting séances to communicate with the dead. Hypnosis was often conflated with these spiritual practices. For instance, some mediums would enter trance-like states, similar to hypnosis, claiming to channel spirits. This association muddied the waters for genuine researchers trying to understand the scientific basis of hypnosis.

Charlatanism and stage shows: Traveling hypnotists would put on grand displays, showcasing their power to make people act against their will or perform embarrassing acts. One famous example is the “clucking like a chicken” stereotype, where a stage hypnotist would seemingly compel a volunteer to behave like a farmyard animal to the amusement of the audience. Such performances, though entertaining, cast a shadow over the therapeutic potential of hypnosis, painting it as a mere parlor trick.

Mind control and manipulation: Tales of sinister figures using hypnosis for nefarious purposes became popular in literature and film. For instance, in movies like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” (1920), characters used hypnosis for malevolent control, perpetuating the idea of hypnosis as a tool for domination.

Media’s role: Beyond film, sensationalized newspaper stories further exacerbated misconceptions. Tales of crimes committed under hypnosis or people being robbed after being hypnotically “seduced” were lapped up by the public, further cementing the fear and misunderstanding around the practice.

While these portrayals and associations certainly added to the allure and mystique of hypnosis, they also posed significant challenges for those trying to establish hypnosis as a legitimate therapeutic tool.

The battle between spectacle and science, between charlatans and clinicians, shaped the public’s perception of hypnosis for years to come.

What is hypnosis, scientifically speaking?

Hypnosis is a psychological state that intertwines elements of relaxation, concentration, and suggestibility. Let’s break it down:

Focused attention: This is an intense concentration on a particular thought, idea, or sensation to the exclusion of external distractions. It’s similar to being engrossed in a book or movie to such an extent that the external world seems to fade away.

Heightened suggestibility: In a hypnotic state, individuals are more open to suggestions. However, this doesn’t mean they can be forced into actions against their will. Instead, they might find it easier to visualize scenarios or follow therapeutic recommendations.

Deep relaxation: Hypnosis often involves a profound sense of calm and relaxation. This isn’t merely physical relaxation but also a tranquil state of mind.

Our current and historic understanding of hypnosis

Understanding hypnosis has been akin to piecing together a complex puzzle. Over the decades, several challenges have emerged:

Definitional ambiguities: Despite its longstanding history, a universally accepted definition of hypnosis remains elusive. Different researchers and practitioners might emphasize various aspects of the phenomenon, making cross-study comparisons challenging.

Standardization issues: With myriad techniques to induce and utilize hypnosis, ranging from direct to more permissive methods, the lack of a standardized approach has been a hurdle in consolidating research findings.

Individual differences: Not everyone responds to hypnosis in the same way. Some individuals are highly hypnotizable, while others might be resistant. This spectrum of hypnotizability, influenced by factors like genetics and personality, adds another layer of complexity to its study.

The neuroscience of hypnosis

With advances in neuroimaging, we’ve begun to glimpse the brain’s workings during hypnosis:

Brain activity patterns: Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) have shown distinct brain activity patterns during hypnosis. Regions like the anterior cingulate cortex and the thalamus showcase altered activity, hinting at the brain’s reconfigured processing during this state.

Functional connectivity: One of the standout findings has been the change in how different brain regions communicate during hypnosis. For instance, there’s increased connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (associated with executive functions) and the insula (related to bodily awareness). This might underpin the intense focus and augmented body-mind connection experienced during hypnosis.

Default mode network: Typically active when our minds wander, the Default Mode Network (DMN) shows decreased activity during hypnosis, suggesting a departure from our usual daydreaming state to a more directed form of cognition.

In essence, as we continue to probe the depths of hypnosis with modern neuroscience tools, we’re steadily demystifying this age-old phenomenon, appreciating its potential not just as a therapeutic tool but also as a window into the intricacies of human consciousness.

The suggestibility conundrum: a double-edged sword

Suggestibility, often synonymous with hypnosis, is a complex trait with profound implications. Let’s delve deeper into the nuances of this phenomenon and its multifaceted impact.

The positive aspects of suggestibility:

Openness to new experiences: A highly suggestible individual may be more receptive to novel experiences or ideas. For example, they might be more inclined to try new foods, explore unfamiliar places, or adopt different perspectives.

Enhanced creativity: Suggestibility can pave the way for a richer imaginative realm. An artist or writer, when in a suggestible state, might conjure up vivid, original ideas, leading to groundbreaking work.

Children and suggestibility: Kids, with their unbridled imagination and lack of preconceived notions, exhibit high suggestibility. It’s why they can effortlessly slip into make-believe worlds or be convinced that their toy is a real-life superhero.

Sleep and suggestibility: The twilight moments just before sleep (hypnagogic state) or right after waking (hypnopompic state) are instances when our defenses are lowered, and our minds are more malleable. It’s in these moments that we might be more open to suggestions or vivid imaginations.

The potential pitfalls of suggestibility:

Creation of false memories: One of the most contentious issues tied to suggestibility is the induction of false memories. For instance, during a therapeutic session, an ill-advised suggestion by a therapist might lead a patient to “recall” a traumatic event that never occurred. Over time, this fabricated memory can become deeply ingrained and perceived as real.

Misleading in legal contexts: In legal situations, witness testimony can be critical. However, a highly suggestible witness might be easily swayed by leading questions, altering their recollection of events. The infamous “McMartin Preschool Trial” of the 1980s serves as a cautionary tale, where suggestive interviewing techniques led children to make false accusations of abuse.

Vulnerability to manipulation: Beyond the realm of memories, highly suggestible individuals might be more susceptible to influence in their daily lives. They could be more easily convinced by persuasive advertisements, political rhetoric, or even fall prey to scams.

While suggestibility underpins the power of hypnosis and can have numerous positive applications, it’s a trait that demands careful handling. Recognizing its potential and pitfalls allows us to harness its benefits while safeguarding against its potential misuses.

The use of hypnotherapy in clinical and healthcare environments

The world of clinical psychology and medicine has long grappled with complex conditions, from the debilitating chains of addiction to the shadowy depths of depression.

Hypnosis, with its unique ability to access the subconscious mind, offers promising avenues for intervention in these challenging areas.

Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Traumatic experiences can leave indelible marks on the psyche, often manifesting as PTSD. Hypnosis can serve as a bridge to access, process, and reframe traumatic memories. By guiding individuals through controlled reliving of traumatic events in a safe environment, hypnotherapy can help desensitize emotional responses and promote healing.

Depression: While depression’s roots are multifaceted, negative thought patterns and beliefs play a significant role. Hypnosis can help individuals identify and challenge these patterns, fostering positive self-perception and breaking the cycle of rumination that often fuels depressive episodes.

Anxiety: The heightened suggestibility during hypnosis can be leveraged to instill relaxation techniques, positive affirmations, and coping strategies in individuals grappling with anxiety. By anchoring feelings of calmness and control, hypnosis can equip individuals to better manage their anxiety triggers.

Phobias: Rooted in deep-seated fears, phobias can be debilitating. Through hypnotherapy, individuals can confront and desensitize their fears in a controlled setting, gradually reducing the phobia’s intensity. For example, someone with a fear of heights might be guided through a visualization of ascending a mountain, with each session making the experience more detailed and vivid.

Addictions: Substance abuse and addictions often arise from a need to escape or numb emotional pain. Hypnosis can help uncover the underlying causes driving the addiction, be it past trauma or unresolved emotional issues. Coupled with positive suggestions for healthier coping mechanisms, hypnotherapy can be a supportive tool in addiction recovery.

Pain management: Chronic pain conditions, from migraines to arthritis, can be debilitating. Hypnosis has shown promise in modulating pain perception, offering a potential adjunctive therapy to traditional pain management strategies. By teaching individuals to visualize their pain and reimagine it in less threatening terms – such as picturing it as a dimming light – hypnosis can provide relief in some cases.

The clinical application of hypnosis taps into the mind’s innate power to heal, transform, and renew.

As research continues and our understanding deepens, it’s evident that hypnosis holds immense promise as a complementary tool in modern healthcare.

However, as with all therapeutic interventions, it’s crucial to ensure that hypnosis is administered by trained professionals in a safe and supportive environment.

The future of hypnosis and hypnotherapy

The vagueness that has traditionally surrounded hypnosis must give way to precision and rigor. Here’s how:

Defining hypnosis: It’s not just about understanding what hypnosis is, but also distinguishing it from other states or techniques. Is it merely deep relaxation, a form of meditation, or something entirely unique? A clear, universally-accepted definition will be the foundation upon which all future research rests.

Measuring success: Qualitative accounts, though valuable, are subjective. To integrate hypnosis into mainstream science, we need tools that offer quantitative measurements. Whether it’s through neuroimaging to observe brain activity during hypnotic states or standardized scales to measure suggestibility, objective metrics are crucial.

Achieving repeatability: Science values consistency. Hypnosis research should be replicable across different settings and populations. This not only validates previous findings but also ensures that therapeutic applications of hypnosis are based on robust evidence.

Protocols and best practices: As with any therapeutic tool, standards of practice ensure safety and efficacy. By establishing clear protocols – from induction methods to post-hypnotic care – we can ensure that hypnosis is administered responsibly and ethically.

Hypnosis holds real, proven, science-backed promise and potential. By treading with curiosity, respect, and scientific rigor, we can unlock doors to cognitive realms previously thought unimaginable. The horizon is vast.

About The Author

Dean Sherzai, MD, PhD

Dr. Dean Sherzai is co-director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program at Loma Linda University. Dean trained in Neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine, and completed fellowships in neurodegenerative diseases and dementia at the National Institutes of Health and UC San Diego. He also holds a PhD in Healthcare Leadership with a focus on community health from Andrews University.

Get more brain science direct to your email inbox

Sign up for the Brain Docs newsletter for weekly recipes, brain teasers, neuroscience facts, podcast updates, and more — for free!