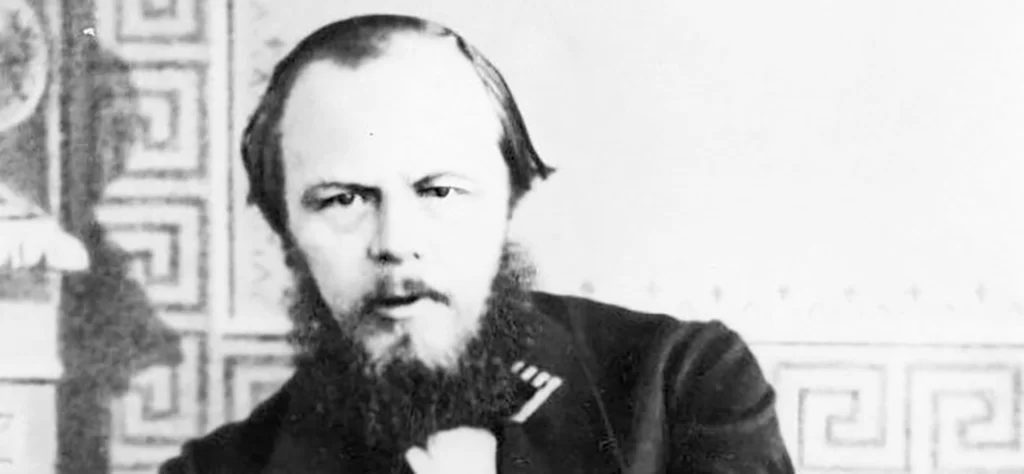

Picture this: 19th-century St. Petersburg, a bustling city filled with the scent of old books and the whispers of revolution. Here, a brilliant young writer named Fyodor Dostoevsky grappled with a curious affliction. The seizures that tormented him throughout his life would become both a source of creative inspiration and an obstacle that he struggled to overcome.

Dostoevsky’s first encounter with epilepsy occurred in his youth and, at the time, he could not have known how profoundly it would influence his existence. His seizures were a terrifying experience, but they also brought him moments of transcendent, almost divine insight. These mystical moments would later find their way into the pages of his literary masterpieces, such as Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov.

As Dostoevsky navigated the challenges of his epilepsy, he became deeply empathetic towards the human condition — particularly the psychological complexities of those who suffer. This empathy would become a hallmark of his work, allowing him to create characters who resonated deeply with readers, helping them understand the human experience in all its rawness and vulnerability.

Today, as we unravel Dostoevsky’s remarkable story, we will also dive into the science behind epilepsy, its historical treatments, and the breakthroughs that have shaped our understanding of this complex condition. So, join us on this journey through time and literature as we seize the moment and uncover the enigmatic world of epilepsy.

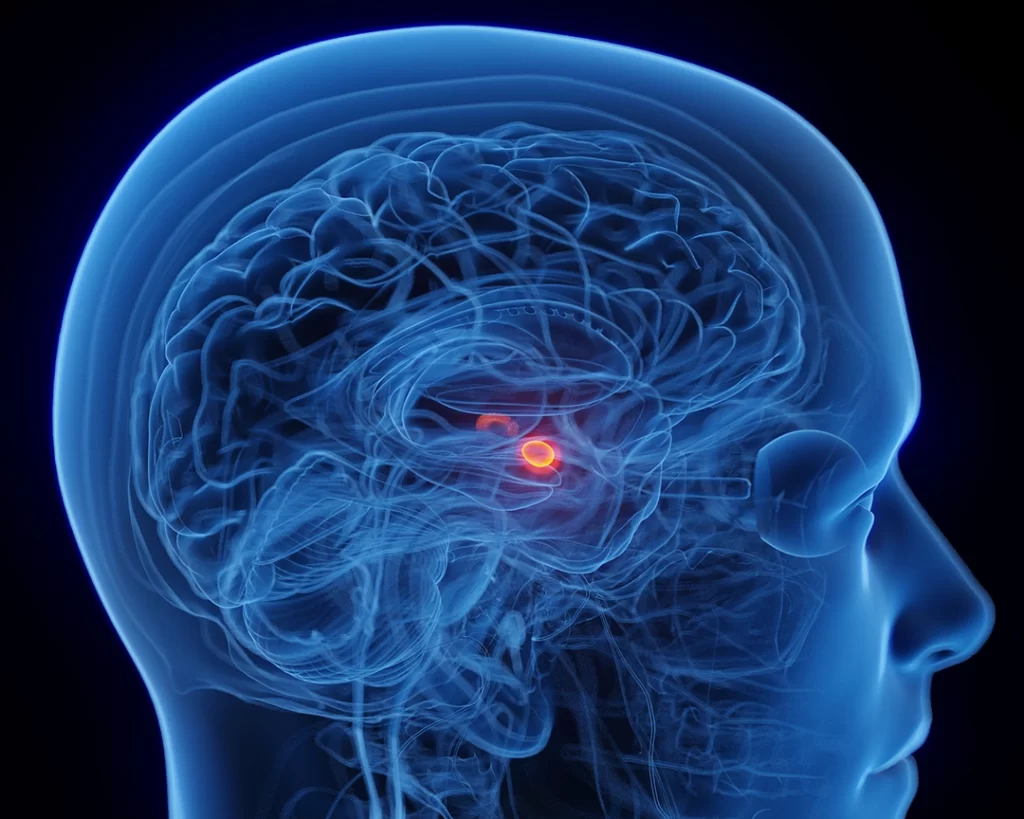

What is epilepsy?

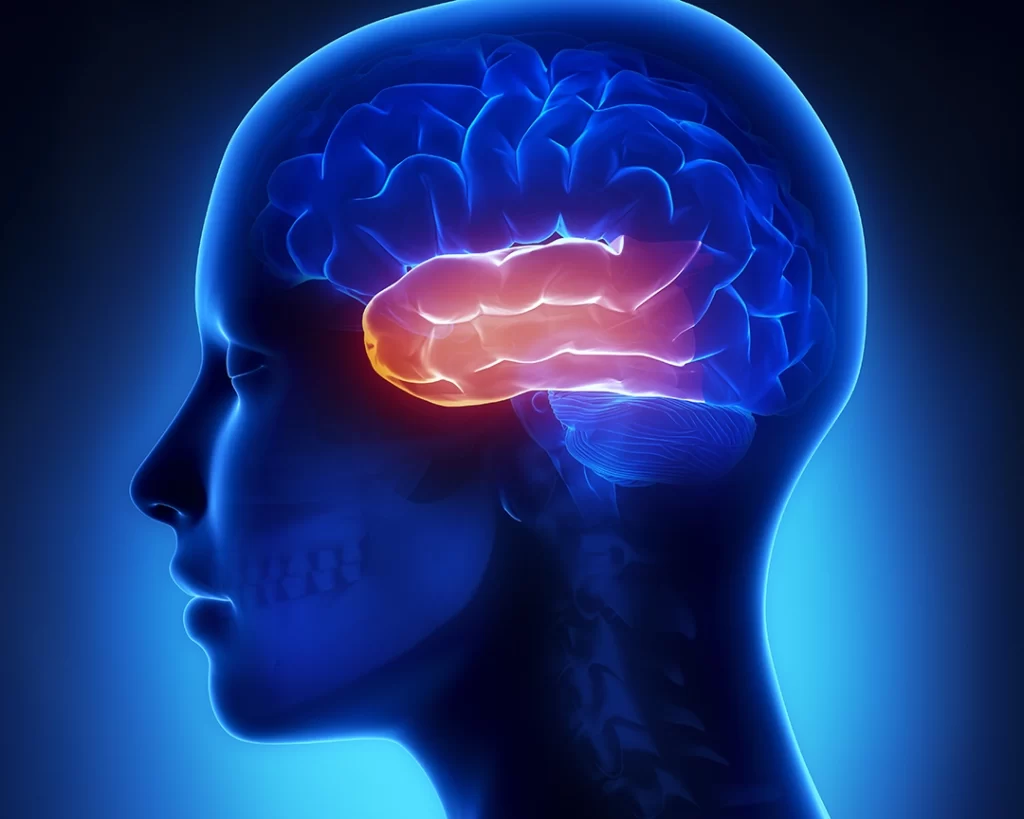

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by a predisposition to recurrent, unprovoked seizures. Seizures are sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbances in the brain that can cause a range of symptoms, from subtle changes in behavior or sensations to severe convulsions and loss of consciousness.

What are the different types of seizures?

Now, let’s delve into the different types and categories of seizures. Seizures are generally classified into two main groups: focal and generalized.

Focal Seizures

Focal seizures originate in a specific area of the brain and are further divided into two categories:

Focal Aware Seizures

Previously known as ‘simple partial seizures’, focal aware seizures do not affect awareness or consciousness. Symptoms depend on the part of the brain involved and can include twitching, strange sensations, or even déjà vu experiences.

Focal Impaired Awareness Seizures

Formerly called ‘complex partial seizures’, these seizures affect consciousness and may cause confusion, memory lapses, or staring spells. A person experiencing this type of seizure may also exhibit repetitive, involuntary movements such as lip-smacking or hand-rubbing.

Generalized Seizures

The second major type of seizures is generalized seizures. These seizures involve both sides of the brain simultaneously and are classified into several types:

Absence seizures: previously known as ‘petit mal seizures’, these are brief lapses in consciousness — often characterized by staring spells — that typically occur in children.

Tonic seizures: these cause sudden muscle stiffness, often leading to falls or injuries.

Clonic seizures: characterized by rhythmic, jerking muscle movements.

Myoclonic seizures: these involve brief, sudden muscle jerks or twitches.

Atonic seizures: also called ‘drop attacks’, these seizures cause a sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to falls or collapses.

Tonic-clonic seizures: previously known as ‘grand mal seizures’, these are the most well-known type of seizure and involve both stiffening of the body (tonic phase) and rhythmic jerking (clonic phase). They can also cause a loss of consciousness and are often the most severe type of seizure.

There are also some very interesting forms of epilepsy, one of which was the type that affected Dostoyevsky most of his life. These include:

Gelastic seizures: these seizures are characterized by sudden, uncontrolled bouts of laughter that may be inappropriate or lack any emotional context. They typically originate in the hypothalamus, a small region deep within the brain, and can be difficult to diagnose as seizures.

Dacrystic seizures: these seizures involve uncontrollable crying or the appearance of being emotionally upset, without any apparent reason. Like gelastic seizures, dacrystic seizures can be challenging to diagnose and are often mistaken for emotional or behavioral issues.

Automatisms: during a seizure, a person may exhibit automatic, involuntary behaviors, such as lip-smacking, fumbling with objects, or repetitive hand movements. These automatisms can be subtle and may not immediately be recognized as seizure activity.

Psychic symptoms: some focal seizures can cause unusual psychic symptoms, such as intense feelings of fear, déjà vu, or jamais vu (a sense of unfamiliarity with familiar surroundings). These symptoms can be disorienting and are often difficult to identify as seizures.

Sensory symptoms: seizures can also manifest as unusual sensory experiences, such as visual hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, or strange sensations in the body (like tingling, numbness, or pain). These symptoms depend on the area of the brain involved in the seizure and can be quite varied.

Aphasia or language disturbances: in some cases, seizures can cause temporary language difficulties, such as an inability to speak, understand speech, or recall words. These seizures typically originate in the language-processing areas of the brain, such as Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas.

Ictal paresis or paralysis: during a seizure, a person may experience temporary weakness or paralysis of a limb or one side of the body. This is often mistaken for a stroke, but unlike a stroke, the symptoms resolve once the seizure is over.

Forced thinking: this rare manifestation involves intrusive, repetitive thoughts that the person cannot control during the seizure. The content of these thoughts can vary and may include specific images, memories, or ideas.

Then there are the intensely emotional seizures – the type that Dostoyevsky experienced – where individuals may experience intense feelings of pleasure, joy, or even orgasm. The specific manifestation depends on the area of the brain involved and the individual’s unique neural pathways – but often originate in the temporal lobe – specifically in the amygdala and insular cortex.

Due to the personal and intimate nature of these symptoms, patients may be hesitant to discuss them with healthcare professionals, which can make diagnosis more challenging.

Pseudo seizures, also known as ‘psychogenic non-epileptic seizures’ (PNES), are a type of seizure that resembles epileptic seizures but is not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Instead, pseudo seizures are thought to be caused by psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, or other emotional disturbances.

Pseudo seizures can be difficult to diagnose as they often mimic genuine epileptic seizures in terms of symptoms, such as convulsions, loss of consciousness, or jerking movements. However, there are some key differences that can help differentiate between the two types of seizures.

For instance, pseudo seizures tend to last longer than epileptic seizures, and the movements are often more rhythmic and less violent. Additionally, patients with pseudo seizures tend to have a higher level of awareness during the seizure, and they may be able to recall what happened during the episode. Pseudo seizures can be very distressing for patients, and they can be difficult to treat. Therapy, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, may be helpful in addressing the underlying psychological factors that contribute to the seizures. It is important for patients with suspected pseudo seizures to receive a proper diagnosis and treatment plan in order to manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

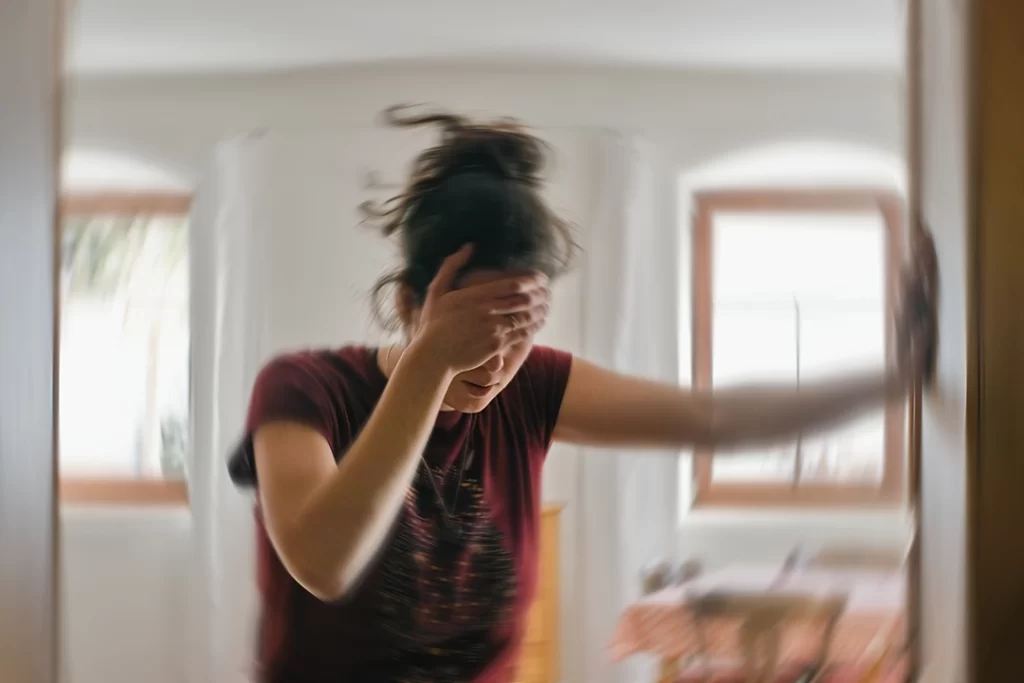

The varying symptoms and severity of seizures

It’s important to note that the intensity and symptoms of seizures can vary greatly from person to person, and some individuals may experience multiple seizure types.

The diagnosis and classification of seizures are crucial for determining the most appropriate treatment options and managing the condition effectively. These are deeply personal experiences that unquestionably affect every aspect of the person’s experience.

A brief history of epilepsy diagnosis

Before the 20th century, our understanding of seizures was limited, and the causes and origins of epilepsy were shrouded in mystery. People with seizures were often viewed through the lens of superstition, fear, and ignorance.

Epilepsy was often attributed to supernatural causes, such as possession by demons, spirits, or divine punishment. In ancient times, people with seizures were believed to be under the influence of evil forces, and exorcisms or rituals were performed to ‘cast out’ the malevolent entity.

Conversely, some cultures viewed seizures as a sign of divine intervention or communication with higher powers. In ancient Greece, people believed that epilepsy was a sacred disease, and those who experienced seizures were thought to possess prophetic abilities. This belief was rooted in the idea that seizures provided a direct connection to the gods or allowed the affected person to receive divine messages.

In medieval Europe, people with epilepsy were sometimes suspected of witchcraft, as their seizures were thought to be a result of spells or curses. Those accused of witchcraft, including people with seizures, faced severe persecution and were often subjected to torture or execution.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, seizures were sometimes linked to madness and hysteria. People with epilepsy were often treated as mentally ill and were sometimes confined to asylums or psychiatric institutions, where they were subjected to various forms of ‘treatment’ that were often ineffective, harmful, or even lethal.

In some societies, epilepsy was seen as a sign of moral weakness or failure. It was believed that seizures were the result of sinful behavior, such as excessive drinking or sexual promiscuity, and that the afflicted person was somehow responsible for their condition.

How seizures affected Dostoevsky: temporal lobe epilepsy

As we delve deeper into Dostoevsky’s experience with seizures, it’s important to understand that epilepsy was still a poorly-understood condition in the 19th century. The mysterious nature of the disorder and the stigma associated with it often left those affected, like Dostoevsky, feeling isolated and misunderstood.

Dostoevsky’s seizures were likely temporal lobe epilepsy, which is known to affect emotions, memory, and sensory perception. His seizures manifested in various ways: sometimes he would lose consciousness and experience convulsions, while other times he would undergo strange perceptual and emotional disturbances. These episodes could be triggered by stress, fatigue, or even specific sensory stimuli such as certain sounds or sights.

Despite the immense physical and emotional toll of the seizures, Dostoevsky found a silver lining in his condition. He described a rare form of ecstatic aura — an intense feeling of joy, harmony, and heightened perception that preceded the onset of the seizure. This aura was so powerful that it felt almost otherworldly. Dostoevsky once wrote, “I would not exchange my disease for all the treasures of the world.”

These moments of ecstatic clarity profoundly influenced his writing. The vivid descriptions of altered states of consciousness, spiritual experiences, and the human psyche in his novels can be traced back to his own experiences with epilepsy. In his novel The Idiot, the protagonist, Prince Myshkin, is an epileptic who experiences similar moments of transcendence during his seizures.

Dostoevsky’s struggle with epilepsy also gave him a profound understanding of human suffering and resilience. This empathy can be seen in his portrayal of characters who grapple with their own physical and mental challenges, as well as their moral dilemmas. His characters, like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, often face moral crises, existential questions, and the consequences of their actions, which Dostoevsky believed were inextricably linked to the human experience.

Other historic figures who experienced epilepsy

Throughout history, there have been several prominent figures who were thought to have epilepsy, either based on historical accounts or retrospective analysis of their documented symptoms. Some of those figures include:

- Julius Caesar (100 BC – 44 BC): the Roman military general and statesman

- Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 – 1821): the French military leader and emperor

- Vincent van Gogh (1853 – 1890): the renowned Dutch painter

- Lewis Carroll (1832 – 1898): the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Harriet Tubman (1822 – 1913): the famous American abolitionist

Diagnosis of epilepsy in historical figures is often speculative and based on the interpretation of historical accounts or documented symptoms.

The epidemiology of epilepsy

Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. The epidemiology of epilepsy helps us understand its prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and distribution among different populations. Here is a comprehensive review of the epidemiology of epilepsy:

Prevalence of epilepsy

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), around 50 million people have epilepsy globally, which corresponds to a prevalence of approximately 6.4 per 1,000 individuals. Prevalence varies across different regions and countries due to differences in demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors.

New cases of epilepsy

The incidence of epilepsy (the number of new cases diagnosed each year) is about 50 per 100,000 people worldwide. The incidence rates vary across different regions, with higher rates reported in low- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries. This could be due to factors like limited access to healthcare, a higher prevalence of risk factors, or differences in data collection.

Age distribution of epilepsy

Epilepsy can occur at any age, but the incidence is typically highest in early childhood and older adulthood. In high-income countries, the incidence is highest among those aged 65 years and older, while in low- and middle-income countries, the incidence is higher in children under 10 years of age.

Here, we describe some of the most common types of epilepsy in children, adolescents, and adults, along with their prevalence and prognosis:

Epilepsy among children

Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS): also known as ‘Rolandic epilepsy’, BECTS is one of the most common epilepsy syndromes in children, accounting for about 15-25% of all childhood epilepsy cases. It typically affects children between the ages of 3 and 13 and is characterized by partial seizures that occur during sleep, affecting the face and throat muscles. Most children with BECTS outgrow their seizures by their mid-teens, with no lasting effects on their cognitive or neurological function.

Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE): CAE affects children between the ages of 4 and 10 and accounts for about 10-17% of childhood epilepsy cases. It is characterized by brief episodes of staring or unresponsiveness, known as absence seizures. These seizures usually last for a few seconds and can occur multiple times a day. In about 70% of children with CAE, the seizures resolve during adolescence, while the remaining 30% may continue to have seizures into adulthood or develop other seizure types, such as generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Epilepsy among adolescents

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME): JME is a common epilepsy syndrome that typically begins in adolescence, accounting for about 5-10% of all epilepsy cases. It is characterized by myoclonic seizures (sudden muscle jerks), generalized tonic-clonic seizures, and sometimes absence seizures. JME is often genetic and requires lifelong treatment, as it typically does not resolve over time.

Juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE): JAE is an adolescent-onset epilepsy syndrome that accounts for about 1–2% of all epilepsy cases. It presents with absence seizures and generalized tonic-clonic seizures. The absence seizures in JAE tend to be longer and less frequent than those in childhood absence epilepsy. JAE usually requires long-term treatment, as the seizures often continue into adulthood and do not resolve spontaneously.

Epilepsy among adults

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE): TLE is the most common form of focal epilepsy in adults, accounting for about 40% of all focal epilepsy cases. Seizures in TLE often originate in the medial or lateral temporal lobes of the brain, and they can present with a wide range of symptoms, including automatisms, altered consciousness, and emotional or sensory disturbances. The prognosis for TLE varies: some individuals may achieve seizure control with medication, while others may continue to experience seizures or require surgery.

Idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE): IGE is a group of epilepsy syndromes characterized by generalized seizures, such as absence, myoclonic, or tonic-clonic seizures, with no identifiable underlying cause. IGE accounts for about 20-40% of all epilepsy cases in adults. The prognosis for IGE is variable, as some individuals achieve good seizure control with medication, while others may continue to experience seizures or face challenges in finding the appropriate treatment.

Epilepsy among the elderly

In the elderly, the incidence of epilepsy is estimated to be around 100-200 per 100,000 person-years. This incidence increases with age, with the highest incidence reported in those aged 80 years and above.

The most common causes of epilepsy in the elderly include stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, and other degenerative disorders of the brain. Other risk factors include hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

Epilepsy in the elderly is associated with higher rates of mortality, cognitive decline, and functional impairment, leading to a reduced quality of life.

How gender affects epilepsy

Epilepsy affects both males and females, with a slightly higher prevalence and incidence among males. The reasons for this gender difference are not yet fully understood.

Risk factors affecting epilepsy

Several factors can increase the risk of developing epilepsy, including genetic predisposition, brain infections (such as meningitis or encephalitis), head trauma, stroke, brain tumors, and perinatal or developmental factors (such as birth injuries or congenital brain abnormalities).

In low- and middle-income countries, additional risk factors include parasitic infections (such as neurocysticercosis) and poor access to prenatal care.

Mortality rates of epilepsy

People with epilepsy have an increased risk of premature death compared to the general population. The mortality rate among individuals with epilepsy is about 2 to 3 times higher than that of the general population. The most common causes of death in people with epilepsy include status epilepticus (prolonged seizures), accidents or injuries related to seizures, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).

The epilepsy treatment gap

Despite the availability of effective antiepileptic medications, there is a significant treatment gap, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The WHO estimates that around 75% of people with epilepsy in these countries do not receive the appropriate treatment. This gap is due to various factors, such as limited access to healthcare, inadequate diagnosis, and a lack of available or affordable medications.

In summary, epilepsy is a common neurological disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. Its epidemiology is complex, with variations in prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and treatment access across different regions and populations. Understanding the epidemiology of epilepsy is crucial for developing effective public health strategies and interventions to reduce the global burden of this disorder.

References to epilepsy in Dostoevsky’s work

Despite adversity throughout his life, Dostoevsky persevered and continued to write. The courage and determination he displayed in coping with his epilepsy allowed him to produce some of the most groundbreaking works of literature. His ability to turn personal suffering into creative inspiration stands as a testament to the indomitable human spirit and serves as an enduring example of resilience for those who face similar challenges.

Crime and Punishment (1866): this groundbreaking novel explores the psychological and moral consequences of a brutal murder committed by the protagonist, Rodion Raskolnikov. Dostoevsky’s personal struggles with the emotional turmoil of his seizures may have contributed to his deep understanding of the human psyche, as seen in the vivid portrayal of Raskolnikov’s inner conflicts and guilt.

The Idiot (1869): the protagonist, Prince Myshkin, is a kind-hearted, innocent man who is often misunderstood by the society around him. Myshkin is also an epileptic, much like Dostoevsky himself. The novel contains vivid descriptions of seizures and explores the impact of epilepsy on Myshkin’s life. Dostoevsky’s own experiences with seizures, particularly the ecstatic aura that he occasionally experienced, likely influenced his portrayal of Myshkin’s transcendent moments during seizures.

Demons (1872): also known as The Possessed or The Devils, this novel is a political commentary and exploration of the destructive impact of extremist ideologies on society. While not directly influenced by his seizures, Dostoevsky’s empathy towards human suffering, a result of his struggles with epilepsy, can be seen in the portrayal of characters who face internal and external turmoil in the story.

The Brothers Karamazov (1880): Dostoevsky’s final novel is an epic exploration of faith, morality, and family dynamics. While the story does not explicitly revolve around epilepsy, the novel delves deeply into the human condition, with characters experiencing intense suffering, existential crises, and moral dilemmas. Dostoevsky’s personal experiences with epilepsy and the emotional turmoil associated with it likely contributed to his understanding of human suffering and resilience, which is reflected in the novel’s themes and characters.

How is epilepsy treated?

The early history of seizure treatment dates back to ancient civilizations, with evidence of treatment attempts found in Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman societies. Early treatments were primarily based on supernatural beliefs, with remedies involving rituals, prayers, and the use of amulets. The Greek physician Hippocrates, however, rejected these ideas, attributing seizures to brain dysfunction and advocating for lifestyle changes and herbal remedies as treatment options.

Throughout the Middle Ages, treatment strategies shifted back to spiritual and supernatural explanations, with exorcisms and prayers being the primary means of addressing seizures.

With the emergence of the Renaissance and the scientific revolution, the understanding of seizures began to evolve, and researchers like Paracelsus started to experiment with chemical treatments. In the 19th century, the first effective anti-seizure medication, potassium bromide, was introduced by Sir Charles Locock, marking the beginning of modern pharmacological treatments for seizures.

Today, seizure treatment has become more advanced and personalized, focusing on addressing the underlying causes and providing effective symptom management. The primary approaches to seizure treatment include:

Anti-seizure medications: also known as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), these medications are the first line of treatment for most people with seizures. AEDs work by reducing the excessive electrical activity in the brain that causes seizures. There are various types of AEDs available, and the choice depends on factors like the type of seizure, the patient’s age, and potential side effects. Some common AEDs include carbamazepine, valproic acid, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam.

Surgery: if ADs are ineffective or cause intolerable side effects, surgery may be considered for patients with a well-defined, localized seizure focus in the brain. The most common type of surgery is the resection of the seizure focus, which involves removing the area of the brain responsible for the seizures. Temporal lobectomy, for example, is a common procedure for treating drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): this is a neurostimulation technique that involves the implantation of a small device under the skin, typically in the chest area. The device sends electrical impulses to the vagus nerve in the neck, which in turn sends signals to the brain to help reduce seizure frequency and intensity. VNS is typically used as an adjunctive treatment when AEDs and surgery are not fully effective or suitable.

Responsive neurostimulation (RNS): RNS is another neurostimulation technique, but it works differently from VNS. A responsive neurostimulator device is implanted in the skull and connected to electrodes placed near the seizure focus in the brain. The device detects abnormal brain activity and responds with electrical stimulation to prevent or reduce the severity of a seizure.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS): in DBS, electrodes are implanted in specific regions of the brain, such as the thalamus, and connected to a pulse generator placed under the skin of the chest. The generator sends electrical impulses to the targeted brain regions, helping to reduce seizure frequency and severity. DBS is typically reserved for patients who have not responded well to AEDs, surgery, or other neurostimulation techniques.

Dietary therapies: certain dietary approaches, such as the ketogenic diet, the modified Atkins diet, and the low glycemic index treatment, have been found to be effective in reducing seizures for some individuals, particularly in children with drug-resistant epilepsy. These diets are typically high in fat and low in carbohydrates, altering the body’s metabolism to use ketones for energy instead of glucose, which may have a stabilizing effect on brain activity.

These treatment approaches can be used individually or in combination, depending on the specific needs of the patient. The choice of treatment depends on factors such as the type of seizure disorder, the severity and frequency of seizures, the patient’s age and overall health, and the potential risks and benefits of each approach. The ultimate goal is to achieve the best possible seizure control with the least possible side effects, improving the quality of life for those living with seizure disorders.

How lifestyle affects epilepsy and its treatments

Lifestyle factors can significantly influence the effectiveness of seizure treatment and the overall management of seizure disorders. By adopting certain healthy habits and making lifestyle modifications, individuals with seizures can potentially reduce their frequency and severity, complementing their medical treatment. Some key lifestyle factors that can influence seizure treatment include:

Sleep: a regular sleep schedule and sufficient sleep are crucial for people with seizure disorders. Sleep deprivation or disturbances can trigger seizures in some individuals. Establishing good sleep hygiene practices, such as maintaining a consistent sleep schedule, creating a relaxing bedtime routine, and avoiding caffeine or screen time before bed, can help improve sleep quality and potentially reduce seizure risk. (Malow, 2004)

Stress management: stress is a known seizure trigger for some individuals. Developing effective stress management techniques, such as deep breathing exercises, meditation, yoga, or engaging in hobbies and leisure activities, can help reduce stress levels and potentially lower the risk of stress-induced seizures. (Novakova, 2013)

Diet: eating a well-balanced diet is essential for overall health and can also have an impact on seizure management. For some individuals, specific dietary approaches, like the ketogenic diet, may help reduce seizure frequency. Additionally, maintaining consistent meal times and avoiding excessive caffeine, alcohol, or sugar intake can contribute to better seizure control. (Neal, 2008)

Medication adherence: strict adherence to prescribed anti-seizure medications is crucial for successful seizure treatment. Skipping doses, taking medications at irregular times, or stopping medications without consulting a healthcare professional can lead to an increased risk of seizures or complications. (Jones, 2006)

Exercise: regular physical activity can improve overall health, mood, and stress levels, which may indirectly contribute to better seizure management. However, it is essential to consult a healthcare professional before starting an exercise program, as certain activities or intensities may not be suitable for some individuals with seizure disorders. (Arida, 2009)

Avoiding seizure triggers: identifying and avoiding personal seizure triggers can be an important aspect of seizure management. Common triggers include flashing lights, specific sounds or patterns, alcohol, or certain medications. Keeping a seizure diary can help individuals recognize and avoid their specific triggers. (Nakken, 2005)

Support systems: having a strong support system, including family, friends, and healthcare professionals, can significantly impact seizure treatment success. Emotional support, understanding, and practical assistance can improve the overall quality of life for individuals with seizure disorders. (Dilorio, 2003)

Incorporating healthy lifestyle habits and modifications can play a significant role in the overall success of seizure treatment. By addressing these factors, individuals with seizure disorders can potentially improve their treatment outcomes and overall quality of life. However, it is essential to consult healthcare professionals before making any significant lifestyle changes to ensure they are suitable and safe for the individual’s specific situation.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s life was marked by a series of challenges and personal tragedies. Born on November 11, 1821, in Moscow, Dostoyevsky was the second of eight children in his family. His father, Mikhail Andreevich Dostoyevsky, was a retired military surgeon who later worked as a doctor at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow. His mother, Maria Fyodorovna Dostoyevskaya, was a kind and devoted homemaker who encouraged her children’s education and intellectual development.

Dostoyevsky’s family life took a tragic turn in 1837 when his mother passed away due to tuberculosis. This event deeply affected the young Dostoyevsky, who was only 15 at the time. Two years later, in 1839, his father died under mysterious circumstances. Some accounts suggest that Mikhail Dostoyevsky was murdered by his own serfs, while others indicate that he died of natural causes.

As an adult, Dostoyevsky married twice, where his first wife is thought to have died of complications of Tuberculosis. He also had two of his four children die in childhood.

Dostoyevsky was also sent to a Siberian prison as a result of his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle, a group of intellectuals in St. Petersburg who discussed and debated literature, politics, and social issues. The group leaned towards liberal and radical ideas, often critical of the Russian government and the institution of serfdom. They were influenced by utopian socialism and sought social reforms in Russia.

In April 1849, Dostoyevsky and other members of the Petrashevsky Circle were arrested on the orders of Tsar Nicholas I, who saw their activities as a threat to the stability of the Russian Empire. They were charged with conspiracy against the government and spreading anti-government propaganda.

After a lengthy investigation, Dostoyevsky and the other defendants were sentenced to death. However, just moments before their scheduled execution on December 22, 1849, the Tsar sent a reprieve, commuting their sentences to various terms of imprisonment and exile. This mock execution had been staged to terrorize the prisoners and serve as a deterrent to others considering dissent against the state.

Dostoyevsky’s sentence was commuted to four years of hard labor in a Siberian prison camp, followed by compulsory military service. He spent his time in the Omsk prison camp, where he endured harsh conditions and physical punishment. This period in Siberia had a profound impact on Dostoyevsky’s life and his subsequent literary works, as it exposed him to the suffering of the common people and led him to explore themes of human psychology, morality, and spirituality.

The Great Dostoyevstky ultimately passed away on February 9, 1881, at the age of 59. The cause of his death was a pulmonary hemorrhage, which was related to a longstanding lung disease, possibly emphysema or complications from his chronic bronchitis.

Dostoyevsky had a difficult life, tentpoled by personal tragedies, financial struggles, and health issues. His epilepsy had a significant impact on his life and his writings. Despite these challenges, he produced some of the most influential works in world literature, including Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Brothers Karamazov, and Notes from Underground.

Sources

Malow, B. A. (2004). Sleep and epilepsy. Seminars in Neurology, 24(3), 301-310.

Novakova, B., Harris, P. R., Ponnusamy, A., & Reuber, M. (2013). The role of stress as a trigger for epileptic seizures: A narrative review of evidence from human and animal studies. Epilepsia, 54(11), 1866-1876.

Neal, E. G., Chaffe, H., Schwartz, R. H., Lawson, M. S., Edwards, N., Fitzsimmons, G., … & Cross, J. H. (2008). The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology, 7(6), 500-506.

Jones, R. M., Butler, J. A., Thomas, V. A., Peveler, R. C., & Prevett, M. (2006). Adherence to treatment in patients with epilepsy: Associations with seizure control and illness beliefs. Seizure, 15(7), 504-508.

Arida, R. M., Scorza, F. A., Peres, C. A., Cavalheiro, E. A. (2009). The course of untreated seizures in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy: A follow-up study. Epilepsy Research, 86(1), 93-97.

Nakken, K. O., Solaas, M. H., Kjeldsen, M. J., Friis, M. L., Pellock, J. M., & Corey, L. A. (2005). Which seizure-precipitating factors do patients with epilepsy most frequently report? Epilepsy & Behavior, 6(1), 85-89.

DiIorio, C., Shafer, P. O., Letz, R., Henry, T. R., Schomer, D. L., & Yeager, K. (2003). Project EASE: A study to test a psychosocial model of epilepsy medication management. Epilepsy & Behavior, 4(5), 507-517