Sleep is a fascinating and essential human experience which influences biology, psychology, and culture, affecting everything from our cognitive abilities to our physical health.

In this piece, I delve deep into the world of sleep and explore intriguing tales from history that highlight the profound impact of sleep and dreams on our lives.

How dreaming has shaped human history

Dreams have long been a cornerstone of human culture, influencing major events, inspiring groundbreaking discoveries, and sparking our earliest thoughts about the afterlife.

The biblical story of Joseph, who interpreted Pharaoh’s dream of seven fat cows being devoured by seven lean cows, demonstrates the impact of dreams. Joseph’s interpretation predicted seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine. In the story, this helps save Egypt from disaster and alters its economic and political landscape.

But dreams haven’t just shaped the history of nations — they’ve also inspired scientific breakthroughs. Physicist Niels Bohr reportedly conceived the model of the atom based on a dream, and inventor Elias Howe resolved the design of the lock-stitch mechanism for the sewing machine through a dream-induced revelation.

Such events highlight the untapped potential of our subconscious mind.

The sleeping patterns of historic figures

Everyone has their own unique sleep patterns, including minds of great historic renown like Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison, Leonardo da Vinci, and Albert Einstein. How they slept influenced their productivity and their lives in general, and so, their sleep shaped history.

Salvador Dali, most famous for his surrealist paintings, had a unique method of tapping into his subconscious mind for creative inspiration. Dali would sit in a chair holding a key over a metal platter. As he fell asleep, the key would drop onto the plate, waking him up. Supposedly, this allowed Dali to hover at the edge of sleep, accessing a state of mind that could inspire unique, dream-like imagery in his art.

I must advise you, the reader, to not try this. Though sleep deprivation may inspire creativity, the long-term consequences are, of course, very dire!

Thomas Edison, the inventor of the lightbulb, was also known for being opposed to sleeping. He considered it a waste of time, and claimed to spend fewer than four hours per night sleeping, opting instead for intermittent naps during breaks from work.

Another historic figure, Nikola Tesla (celebrated for his contributions to electricity supply systems), famously had a mental breakdown at the age of 25 after regularly sleeping for a mere two hours each night. He managed to improve his sleeping schedule, though, and he was healthier for it. Tesla worked for many more decades, and died in 1943 at the each of 86.

Elsewhere in 1943, Winston Churchill was serving his first term as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom amid the throes of the Second World War. Churchill was quite the opposite of Tesla and Dali — he greatly valued sleep, so much so that he had a bed installed in the Houses of Parliament for afternoon naps. Perhaps it was these short ‘power naps’ that helped him stay sharp and strategic through globally-tumultuous times.

Historic disasters influenced by a lack of sleep

There are a number of tragic disasters throughout history thought to have been caused at least partially by a lack of sleep amid those involved:

1. The Challenger Explosion (1986): key decision-makers had gotten minimal sleep the night before due to a launch scrub, leading to poor judgement.

2. Exxon Valdez Spill (1989): the crew had been working round-the-clock with very little sleep for 16 hours prior to the disastrous oil spill.

3. American Airlines Flight 1420 Crash (1999): fatigue and long working hours contributed to the crash, with the official report citing “impaired performance resulting from fatigue.”

4. Metro-North Train Crash (2013): the train conductor failed to stop the train due to fatigue from undiagnosed severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This incident emphasizes the importance of screening for sleep disorders, particularly for individuals with life-or-death responsibilities.

5. Hoboken Train Crash (2016): similar to the Metro-North Train Crash, the conductor’s fatigue from undiagnosed OSA was deemed the probable cause of the accident. This incident led to improved screening for OSA and other fatigue-inducing sleep disorders in the transportation industry.

6. Libby Zion Law Reform (1984): a tragic case unfolded in New York City when a couple of overworked, sleep-deprived residents failed to care for an 18-year-old patient, Libby Zion, due to medical errors born of fatigue and long shifts. This incident led to Zion’s death, and, as a result, the establishment of the Libby Zion Law by the Bell Commission, radically altering the structure of medical residencies nationwide. The law capped work hours to a maximum of 80 per week and mandated the supervision of residents, balancing the need for both adequate sleep and patient safety in medical training.

The undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea afflicting the conductors involved in the Metro-North Train Crash Hoboken Train Crash is one example of a sleep disorder. Sleep disorders disrupt the normal sleep-wake cycle, impairing quality of life and overall health.

Treatments for sleep disorders vary depending on the type and severity of the disorder. Techniques like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be integral for sleep disorder management. CBT traces back to the groundbreaking work of psychologists like Aaron T. Beck and Albert Ellis during the mid-20th century. Their work has helped countless people regain control over their sleep patterns and improve their overall quality of life.

So, we’ve seen how healthy sleeping patterns positively affect history, and how a lack of sleep can lead to disaster — but why? What’s the neuroscience of sleep?

How does sleep work?

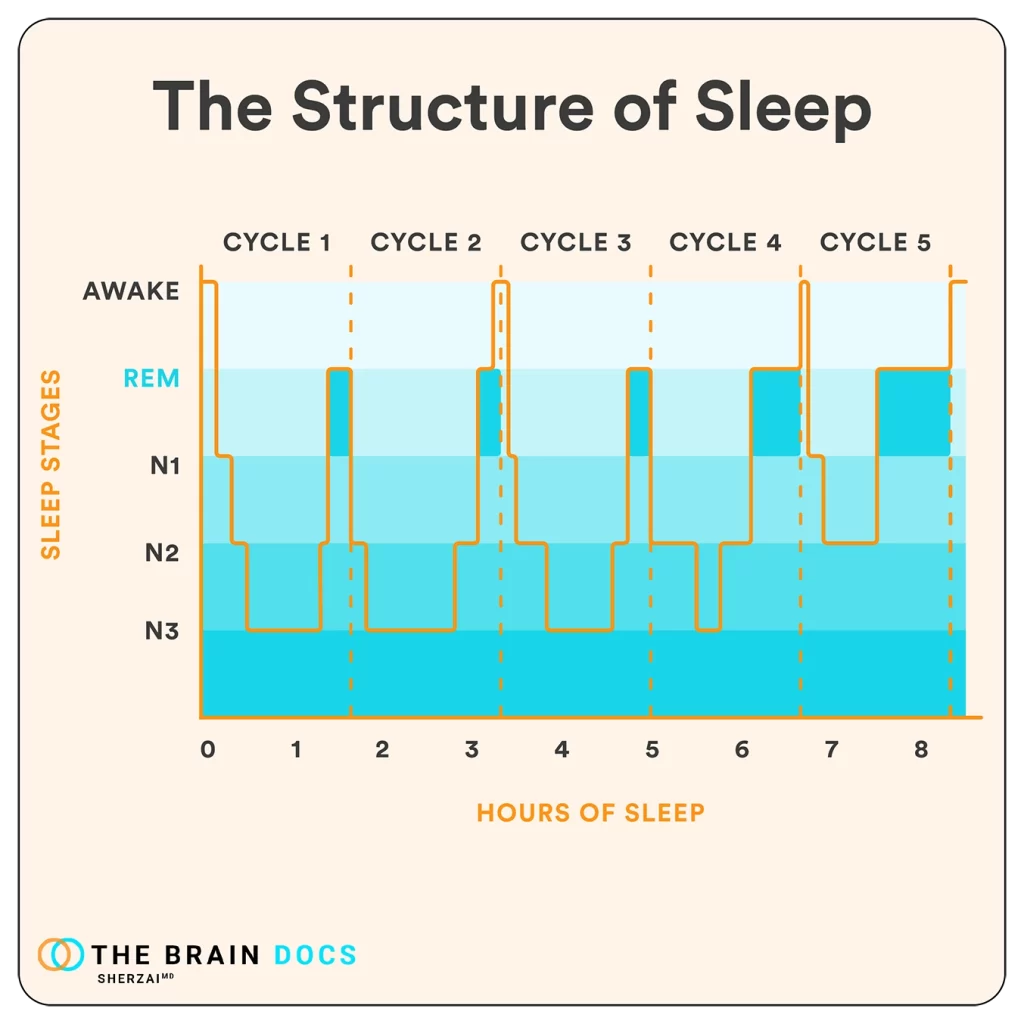

Sleep is not a single-phase state but a multistage journey that unfolds throughout the night. It consists of different stages, each distinguished by its unique physiological and neurological characteristics. Typically, we cycle through these stages four to five times each night. Each sleep cycle lasts roughly 90 minutes.

The first stage of sleep — known as ‘N1’, or the ‘light sleep’ stage — is the transition from wakefulness to sleep. During N1, brain waves slow down, and you may experience a sensation of falling or muscle contractions. It’s a short stage, usually lasting just a few minutes.

As we descend deeper into sleep, we enter the ‘N2’ stage. Our brain waves continue to slow down, interspersed with short bursts of activity known as sleep ‘spindles’. These spindles play an important role in sensory processing and long-term memory consolidation. The N2 stage occupies approximately 50% of our total sleep.

Transitioning from N2, we arrive at ‘N3’, or ‘slow-wave sleep’ (SWS). This stage is the deepest and most restorative phase of sleep. Brain waves slow down even further. During this stage, the body repairs and regrows tissues, builds bone and muscle, and strengthens the immune system.

After N3, we move into the ‘rapid eye movement’ (REM) stage, the phase most associated with intense dreaming. In REM sleep, our brain waves mimic the activity seen during wakefulness, creating a unique paradox of a sleeping body with an active mind. REM sleep stimulates the brain regions used in learning and is thought to be involved in the brain’s processing and consolidation of experiences and memories.

Going through these sleep stages multiple times each night is crucial. Each stage serves unique restorative functions, contributing to physical health, brain functions, and memory processing. They reflect a well-orchestrated sequence of biological events that rejuvenate us nightly and maintain our overall health and well-being.

Why do we sleep?

We’ve evolved many biological phenomena which help with our survival. Sleeping is one of them. Dreaming might be another, if you consider the ‘threat simulation theory’. The theory proposes that dreams can prepare us for real-life dangers by harmlessly ‘simulating’ potentially-fatal threats.

And this is just one of many cognitive benefits of sleeping. Here are a few more.

The glymphatic system: how sleep cleanses the brain

One of the most remarkable physiological functions of sleep is the role it plays in ‘cleansing’ our brains through a system known as the glymphatic system. This system was discovered relatively recently in 2012 by neuroscientist Maiken Nedergaard and her team at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

It’s named after the glial cells which facilitate the process, and functions similarly to the lymphatic system, which drains waste from the rest of the body.

During our waking hours, while our brain cells are hard at work, they create waste products, including potentially-harmful proteins such as beta-amyloid, a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

These waste products can accumulate in the spaces between brain cells. However, the brain has a unique and efficient way of dealing with this buildup, primarily during sleep.

When we enter the realm of sleep, our brain cells shrink by about 60%, increasing the space between them. This expansion allows cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) — a clear, colorless fluid found in the brain and spinal cord — to flow more freely.

The flow, driven by the glymphatic system, flushes out the accumulated waste into the bloodstream, which later gets eliminated via the liver.

This cleansing process is like a dishwasher for our brains, maintaining the health and function of our most vital organ.

The glymphatic system is nearly ten times more active during sleep than in wakefulness, emphasizing how important a good night’s sleep is for maintaining cognitive health.

This system’s function also highlights the potential dangers of chronic sleep deprivation, which can lead to an accumulation of harmful waste products in the brain and may contribute to the development of neurodegenerative diseases.

How sleep helps with processing emotions

Dreams can evoke strong emotions and allow us to re-experience and process emotionally-charged events.

This emotional memory processing may contribute to the consolidation of emotional memories, helping us regulate and understand our emotions better.

This might have been a particularly essential function all throughout history, helping us cope with the stress and trauma associated with wars, famines, and pandemics.

How sleep consolidates our memories and thoughts

Sleep doesn’t just help process traumatic, stressful experiences — it also plays a crucial role in the consolidation of more ‘regular’ thoughts and memories.

When we sleep, our experiences are transformed from short-term memories into long-term knowledge. During the REM (rapid eye movement) phase of sleep, our brains are highly active, processing and categorizing all the stimuli and information we come across during the day.

REM sleep contributes to the consolidation of procedural and spatial memory: the ‘how’ and ‘where’ of learning. For instance, if you’re learning to play a musical instrument, REM sleep is vital for improving your performance.

The deep, slow-wave sleep (non-REM sleep) also plays a significant role in memory consolidation, particularly declarative memories: the ‘what’ of learning, such as facts or events. During this phase, the hippocampus — that’s the brain’s memory center — replays the day’s events, strengthening the neural connections that form memories.

Beyond merely storing information, sleep also aids in the process of memory integration. This is where separate pieces of information are linked together, forming the basis for creative thinking and problem-solving. Thus, sleep not only helps us remember, but can also enhance our capacity for innovation and insight. Sleep’s role in memory and thought consolidation underscores its importance in cognitive performance and learning, adding yet another reason to prioritize quality sleep.

Sleep disorders and their impact on the brain

Knowing how important sleep is for cleansing the brain, consolidating memories, and processing traumatic experiences makes it clear why sleep disorders can be detrimental to our health. Having little or low-quality sleep can impede our physiological and cognitive functions.

Sleep apnea, characterized by repeated interruptions in breathing during sleep, can result in fragmented sleep and reduce the time spent in deeper stages of sleep, which are crucial for brain cleansing and memory consolidation. Also, the intermittent drops in oxygen levels that occur in sleep apnea can have detrimental effects on brain health.

Insomnia — that’s a chronic difficulty with falling or staying asleep — can significantly reduce total sleep time, limiting the glymphatic system’s opportunities to clear out brain waste. This deprivation can also lead to cognitive impairments due to insufficient memory consolidation and integration.

Restless leg syndrome and sleep-related leg cramps can cause frequent awakenings, interrupting your progression through the different stages of sleep and negatively impacting all the cognitive benefits healthy sleep provides.

Over time, untreated sleep disorders may increase the risk for cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases, further emphasizing the importance of diagnosing and treating these conditions. Regular monitoring of sleep patterns, a healthy lifestyle, and adherence to treatments are all key factors in maintaining good sleep hygiene and promoting optimal brain health.

When we think about health, the binary of ‘diet’ and ‘exercise’ are often the most widely-cited factors, but sleep should be prioritized right alongside them. After all, without sleep, we can’t effectively maintain a healthy diet, and we most definitely can’t exercise.

References

Shanon, B. (2003). The Antipodes of the Mind: Charting the Phenomenology of the Ayahuasca Experience. Oxford University Press.

Revonsuo, A. (2000). The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(6), 877-901.

Walker, M. P. (2017). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Scribner.

Walker, M. P., & van Der Helm, E. (2009). Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological bulletin, 135(5), 731.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Descharnes, R., & Néret, G. (2013). Salvador Dalí: The Paintings. Taschen.

Hobson, J. A., & Friston, K. J. (2012). Waking and dreaming consciousness: Neurobiological and functional considerations. Progress in neurobiology, 98(1), 82-98.

Mitler, M. M., Carskadon, M. A., Czeisler, C. A., Dement, W. C., Dinges, D. F., & Graeber, R. C. (1988). Catastrophes, Sleep, and Public Policy: Consensus Report. Sleep, 11(1), 100–109.

About The Author

Dean Sherzai, MD, PhD

Dr. Dean Sherzai is co-director of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Program at Loma Linda University. Dean trained in Neurology at Georgetown University School of Medicine, and completed fellowships in neurodegenerative diseases and dementia at the National Institutes of Health and UC San Diego. He also holds a PhD in Healthcare Leadership with a focus on community health from Andrews University.

Get more brain science direct to your email inbox

Sign up for the Brain Docs newsletter for weekly recipes, brain teasers, neuroscience facts, podcast updates, and more — for free!